Issue 08. Sun Moon Stars.

The Vanity Papers Oxford Literary Review

Selection © The Vanity Papers

Copyright of works rests with authors and artists

The Vanity Papers Oxford Literary Review

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Rupa Wood

BUSINESS DIRECTOR: Catherine Digman

EDITOR: Biddy Vousden

“the love that moves the sun,

the moon, and other stars”

(Paradiso, XXXIII, 145)

LISA BLACKWELL is a writer and performer. Her short fiction and poetry have appeared in journals, anthologies and online, and her first prose poetry chapbook, ‘How it will happen’, was the Three Trees Portfolio Award winner 2022 (published by Maytree Press) @lisablackwellwrite

SHELLEY BROOKS is a NYC-based graduate of the Oxford Mst creative writing program. Her theatrical work as a writer and performer has appeared at The Tank, HERE Arts Center, Dixon Place, The Vino Theater, and The Metropolitan Room. Her criticism has been published in Paper Magazine, Slate, Roger Ebert, Reverse Shot, and more, and an upcoming piece will soon be published in The Forward. @ohlookitsshelleybrooks

JOSH COBLER is a second BA student in law. Before coming to Oxford, he studied anthropology in California. Outside of academia, he loves staying engaged in social justice issues, traveling to new places, trying new foods, day dreaming, and writing.

CATHERINE DIGMAN is reading History at Harris Manchester. In her heart she knows that History is the greatest fiction of all time. @CatherineDigman

SARA FARNWORTH is studying Applied Landscape Archaeology from Campion Hall, where powerful inspiration is around every corner.

MAREE JACOB is an avid reader, enthusiastic writer and general practitioner based in the east of England.

HANNAH LEDLIE is an Edinburgh-born, Manchester-based writer. Her work has appeared in Ambit, Gutter, Magma, Butcher’s Dog, and New Writing Scotland.’

TINA JUUL MØLLER is a Copenhagen-based poet, learner, raging feminist.

SANDEEP KUMAR MISHRA is an artist, an author, a teacher and an editor. He has published 15 books, translated into more than 20 international languages, shortlisted for more than 50 international literary and arts awards and has been published in all six continents inhabited by humans. www.sandeepkumarmishra.com

THEMBE MVULA is a South African writer and poet; an alum of the Roundhouse Poetry Collective, Barbican Young Poets and the inaugural Obsidian Foundation retreat. She self-published her debut pamphlet, We that Wither Beneath, in 2019.

LUCY POOK is a multi-disciplinary artist, whose media dance between drawing, painting, poetry, stand-up comedy and performance art, to create a holistic practice that evokes the Gombrich stance of “There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.” @pookpayingattention

RICK LONGLEY whilst writing under the pen name of Skyler Clarke, in his teenage years, wrote around 300 poems. He wrote poems in Paris, in Moscow, and in Buenos Aires. After a seven-year hiatus, under his (almost) real name, Rick shares his poetry with joyful trepidation. Perhaps, in a former life, Rick would have been a full-time poet-adventurer-extraordinaire, earning his keep by fencing with (hypothetically) rapiers and (more realistically) with words. For now, he crunches numbers for a film company. Wrestling with his arithmophobia, Rick finds joy in the work as a loyal servant of Christ Jesus. ‘[…] God had greater things in store if they would only learn to put him first’.

LAURA THEIS writes in her second language. Her work appears in Poetry, Oxford Poetry, The Irish Times, Poetry Birmingham, Magma, Rattle, Mslexia, Berlin Lit, etc. Accolades include the Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize, Oxford Brookes Poetry Prize, AM Heath Prize, Mogford Prize, and a Forward Prize nomination. Her debut how to extricate yourself, an Oxford Poetry Library Book-of-the-Month, was nominated for the Elgin Award and won the Brian Dempsey Memorial Prize. A Spotter’s Guide To Invisible Things received the Live Canon Collection Prize, and the Arthur Welton Award from the Society of Authors. Her latest publications are Introduction To Cloud Care (Broken Sleep Books) and her forthcoming children’s debut Poems From A Witch’s Pocket (Emma Press).

RUPA WOOD is a multi-disciplinary artist exploring the philosophy of miraculous and commonplace magic. Her publications include Varsity Publications Cambridge, The London Magazine, The Oxford Magazine, Loft Books and The Oxford Review of Books. rupa@thevanitypapers.com

KATE ZIPPEL is a Cherokee Native American whose people come from the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina. She is studying for a DPhil in Evidenced-Based Health Care at Kellogg College and a Professional Certificate in Narrative Medicine from Columbia University. She works as a General Practitioner in remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory of Australia.

SOLARIZED TINSEL PHOTOGRAM

LISA BLACKWELL

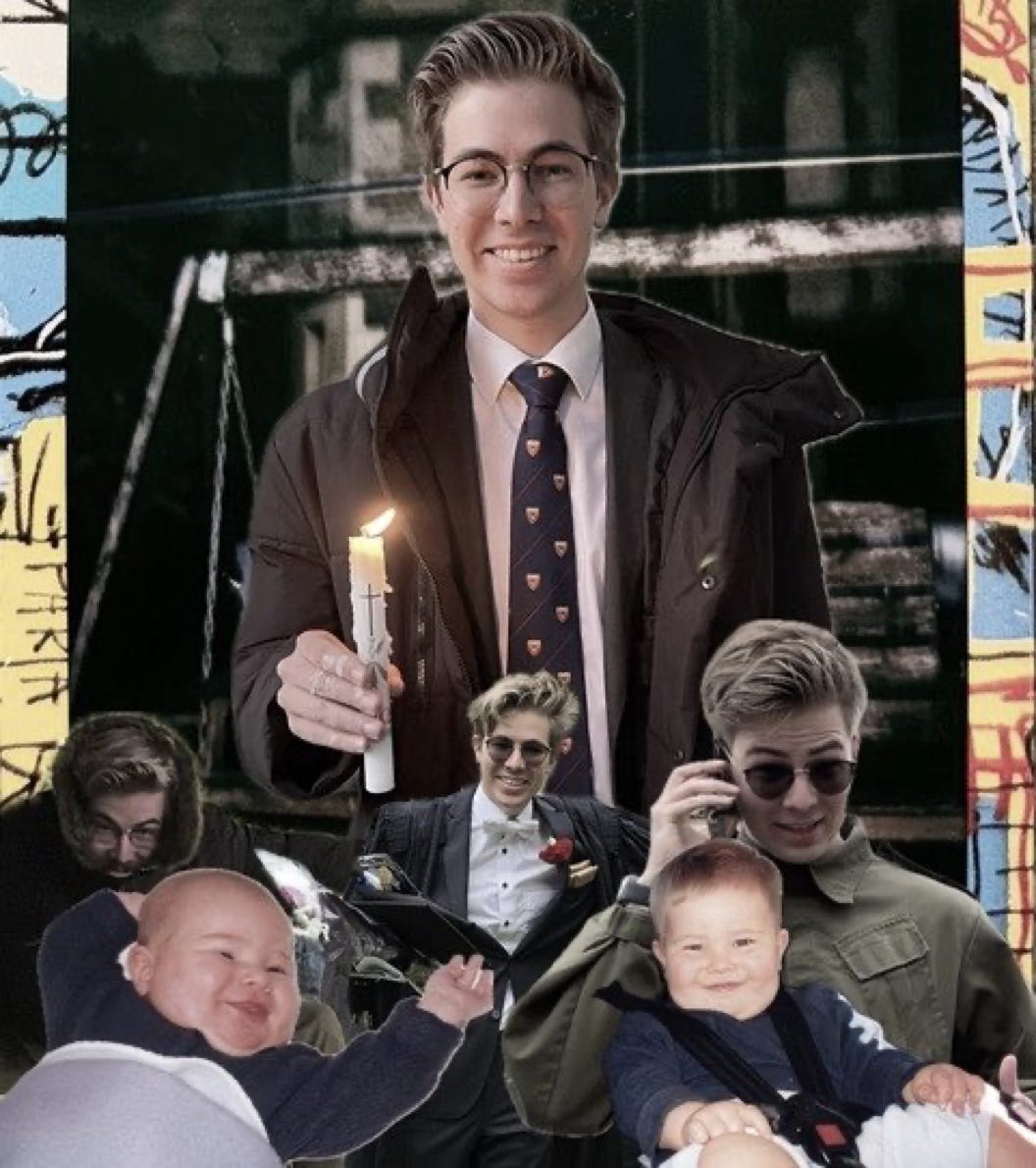

JOSH COBLER

WHO MADE THE SUN RISE

the sunset

As I sat in your car, I couldn’t help but think about how we were staring at the same sunset. The setting sun painted the sky with streaks of orange and purple across its deep blue canvas. Gentle ocean waves rocked back and forth into the hills below us, reflecting back the fading red hues of the sun’s descent.

Your right palm held the steering wheel in place as we continued down the highway. There was not a single car in sight, a rarity for this stretch of Highway 1. The complete emptiness that surrounded us felt so rare. We had traded the ringing bells of cable cars, the bright city lights, and the busy wharf for the gentle hum of your car under a breathtaking sunset. For a few minutes, all I could do was admire the beauty of this place, sharing it only with you.

I looked over at you. Your eyes were starting to glaze, and you didn’t notice me turning to look at you. Or maybe you did, but you didn’t turn to look back at me. The setting sun beamed brightly in the rearview mirror, and that light bounced back onto you and your almond-colored eyes.

For miles, we didn’t exchange a single word. It had been a long day, which is what I kept telling myself to rationalize the silence between us. Every time I would open my mouth and take a breath, trying desperately to fill the noiseless void, something about your disinterested gaze kept me quiet. I resigned myself to just looking at hills and the ocean and the sky, hoping you found it as beautiful as I did. I so desperately wanted to turn to you and say, Look how incredibly beautiful this sunset is! Isn’t this everything you’ve ever dreamed of? And then you would turn to me and say, Of course. It’s a land flowing with milk and honey! But instead, I kept quiet and didn’t say a word.

You and I had a lot on our minds, and we were dreaming of the same things, just with different people. You were thinking of her long, silky hair, glistening as the light from San Francisco Bay reflected back onto her. You were thinking of her eyes, the same shade of brown as the coffee she would make you every morning when you’d meet at dawn to watch the sunrise together. You were thinking of her smile, her laugh, the way she says your name, the last thing she said to you, how you just want to have her.

But this whole time, I was thinking of you, and how I can’t have you.

I waited for you in my room that night after rinsing off the pain as best as I could. I prepared everything for your arrival, making sure that everything was put in its place within my tiny apartment. Then, I heard you knock on the door. “Hey, it’s Samuel,” you said, walking into the little gray room. You stood awkwardly next to the side of the couch, hesitating for a second until you decided it was okay for you to sit down right next to me. Then you reached into your pocket and pulled out the shiny, metal vape pen, connected to a brand-new cartridge of pure cannabis oil, and handed it to me.

I rolled it in my fingers, watching the oil slink to one side of the mouthpiece before I turned it around and the viscous, yellow fluid returned to center. I put the pen up to my lips, inhaled deeply, then exhaled a large cloud of white smoke. It swirled out of my mouth, spiraling towards the side of the room and escaping through the crack in the window. I passed the pen to you and you attempted to repeat the same motions—you put the pen up to your lips and inhaled for just a few seconds too long. “Shit,” you said in between coughs as I burst into laughter, puffs of smoke shooting out from your mouth and nose, shattering the silence that filled the room. You handed the pen back to me, and I took another hit.

This had become a weekly ritual for the two of us—our Sabbath where you would sit on my couch, smoke weed, and talk about all the funny, weird, and chaotic things that would happen to us over the course of each week. It was usually my only chance to ever find out more about you—about all your hopes and fears, all that you had achieved and hoped to do. But it was also when you told me about her.

“I was with Bella again last night,” you said as you brought the vape pen back up to your lips. I turned over to look at you, slumped into the arms of the couch, your eyes bright red. “We met up to get dinner together and then I went back to her place.”

“Oh wow, look at you,” I teased.

“The craziest part though,” you started, “was that we spent so much time talking about our pasts. It felt like we really had a connection.” You paused for a few seconds. “It’s funny, because I’ve never felt so comfortable opening up to someone before.”

I couldn’t even imagine what you must have felt to finally be so open or what it was about her that let you put your guard down. You were always so closed off and reserved, and rarely would you go beyond the usual pleasantries of asking about our weeks. You would tell me what’s really going on in your life, but only after weeks and weeks of me prodding about how your life has been, as I would try to probe out what else was on your mind beyond what you would openly share. You had never spoken to me about who you were and what you had experienced before I met you, even after I had told you everything that there ever was to know about me. But with her, things were different. The two of you hit things off so quickly.

“Man, we even talked about some things which I would never just tell anyone about,” you said. You paused, moving the metal vape between your fingers, before you looked right into my eyes. Even in my dim, gray apartment, your eyes beamed with an ebullience I’ve never seen from you before. “It’s just so great to have someone I can really trust, y’know?”

“Wow, that’s… that’s really amazing. I’m really happy for you.”

***

You had known her for a year, but she was someone you just watched from afar. Last year, you wrote everything off so quickly, no matter how many times I told you that you that you shouldn’t think that you don’t have a chance with her. You’re a really special person, I remember having told you one night when you drunkenly stumbled into my apartment, telling me that you so desperately wanted to be with her but there was no chance that she would ever love you back. That’s not true, I told you, I really think it could work out.

For the last few months, you told me every detail of every interaction that you both had. You had started talking to her more whenever you could, whether that was straining to find something funny to text her about or exchanging an ephemeral hello on the street. But just last week, you bumped into her at an independent café you’d never been to before, running in to grab your usual lunch of a warm panini and a bottle of iced tea. “Funny running into you here,” you had said to her, after mustering up the courage to go to the table she was working at. “Do you come here often?”

“All the time,” she said, closing her book before inviting you to sit with her. As you sat down, you did your best to be more attentive than ever, noticing the stickers of the beach and the ocean on her notebooks and the freshly brewed coffee flavored with milk and honey sitting in a ceramic glass on the table. She told you that, on her bucket list, she always wanted to be a barista who could make gourmet coffees, so she would sit in this boutique café every afternoon with her books and her notebooks trying to soak up the aroma of coffee beans to inspire her. “Are you a big coffee person?” she asked you.

“I am, actually,” you responded. “I can’t live without it.” But we both know you couldn’t stand the taste.

“That’s perfect! I finally decided to get a fancy new espresso machine, but I needed someone to help me taste test!” And just like that, she had invited you over, bright and early, to try out her new caffeinated creations.

The next morning, you rang the bell to her apartment door. It was so early—before seven o’clock in the morning—that the winter sun was only just rising. As she opened the door, you immediately noticed the distinctive aroma of coffee beans and roses. A soft breeze blew through her window, and her soft silk curtains billowed behind her as the aromas swirled across the room.

“I’m trying to make a latte as beautiful as the ones at the café,” she said. She put the ground espresso beans in the portafilter of the machine, jerking it a little too far and hitting the steam button instead. “Sorry, I’m very new to this,” she said, as she poured milk into a metal frothing pitcher while the espresso dripped out into her glass. Her attempts to froth the milk were even less successful, as a cloud of white steam shot out from the machine and the milk splattered all over the kitchen counter. But at the end of this chaotic, messy attempt at a homemade latte, she sprinkled a few pink rose petals on the very top. Apologizing profusely, she handed it to you. “It’s probably really bad,” her voice coming almost to a whisper, “but tell me what you think. Don’t hold back.”

You took a sip. The truth was, you still couldn’t stand the taste of coffee. “This tastes amazing,” you said, forcing yourself to take sip after sip until you finished the entire glass.

Then only days ago, just as I told you, things began truly working out in your favor. The two of you had met in her room one Saturday morning at the beginning of February. She made both of you coffee as she often did, adding rose petals to the top as always. It was always funny to me that she did that; I guess she couldn’t tell that you really didn’t like the taste.

“Hey, Bella,” you said on that fateful early Saturday morning, forcing yourself to finish the whole cup. “Why don’t we do something different tomorrow?”

“What do you have in mind?” she asked you.

“Why don’t we go to Santa Cruz?” you offered. “You’ve always talked about wanting to go to the Boardwalk, so why don’t we? Bright and early. I bet the sunrise over the beach would be absolutely beautiful.”

Although a bit shocked by your sudden spontaneity, she agreed. The next day, the two of you made the hour-and-a-half-long drive out there. By the time you made it, the sun was just rising. You walked on the beach together, watching the misty air dissipate and the sun peek up over the ocean. At some point, the two of you sat down on the sand and turned your attention to the sunrise. You and Bella watched the waves slowly and gently caress the beach. You dipped your feet in the ocean, holding her hand and trying not to let the world know that her reflection made your heart flutter. You slowly and gently ran your fingers through her dark chocolate-tinted hair, everything in the world stopping as you looked into her eyes. Then, you found courage deep within your heart, and you slowly and gently moved your lips to hers.

The two of you remained like that, dipping your feet into the ocean, both of you swirling your feet around in the water. And as you did, the glow of the morning sun bounced off the water and back onto you.

the darkness

Do you remember what you said to me when you came into my room the morning after your beach adventure? I remember seeing you burst into my living room. Your skin was radiant. You were glowing, and the glow from your light bounced off my bedsheets and lit up the room. I was still in bed, my eyes struggling to stay open when you came into my room. As you did, I forced myself out of bed to make myself my morning cup of tea. I offered to make you tea as well, just as I used to do whenever you would come into my room in the morning and we’d talk about something random and stupid before it was time to take on the day. You declined, saying Bella had already made you coffee before you came into my room. But you don’t even like coffee, I remember saying to you. I’m starting to learn to love it, you said to me.

“You’re really not going to believe what happened to me yesterday,” you said, still trying to catch your breath.

“Try me.”

You told me how, when you got back to the city and went your separate ways, that you just wanted to spend more time together. That evening, you texted her, saying how much you appreciated spending time with her and how you’d love to have more time with her. She responded with just three words: Then come over. When she did, you dropped everything you were doing and ran straight out the door, straight to her building. You found your way in, knocked on her door, and when she opened it, instead of asking you if you wanted coffee, she threw herself onto you, your lips locking together, her body pressed up against yours. You pulled her leg up to your hip, and then you threw her on the bed. Right away, her clothes came off. You jumped onto the bed with her, and she pulled off your shirt, unbuckled your belt, unzipped your pants, and the two of you did the things you had always wanted to do for the last year, the things you always wanted to do with her.

You told me that this is what you always imagined California would be like. You told me that even though the girls you loved back home were just as beautiful as Bella, what you two had was something else, something different, something breathtaking. That was the word that you used to describe it all, the word you used to describe her: breathtaking, your mouth dripping with milk and honey as you said it. You told me that, after it was all over, the two of you spent the night in her bed, curled up together, your legs over hers, your arm hanging over her heart. And then a little bit after you had fallen asleep, she shook you awake, saying she was ready to do it all over again. You told me that it was the best sex of your life, that after mediocre one-night stands and a less-than-thrilling relationship or two, this took your breath away. You described so many of the details to me. And you told me that you were still trying to process all of it, because you just never expected anything like that to happen any time soon, let alone with her.

***

“Wow, that’s…” I started, pausing to try to think of the words that I wanted to say to you. I took another hit. “That’s really amazing. I’m really happy for you.”

You paused again, unsure of how to respond. I wasn’t sure what you were expecting at the time—did you want me to share in the excitement that you felt? Because as much as I tried, I just couldn’t. “You know,” you said that night, “I really have feelings for her. And it’s just so nice to have someone who cares about me just as much as I care about them.”

The words stung when you said them. “Wow, that’s…” I repeated, “that’s really amazing. I’m really happy for you.”

We sat in silence for a few seconds before you broke the next piece of news to me. “I think I’m gonna talk to her about making this official. I’d really like to date her long-term. I feel like we’re so compatible that this could definitely work out.”

I looked down at the floor in front of me, careful to look far enough away that I couldn’t even see you in my periphery. You didn’t know what else to say. So you didn’t. Usually when we’d run out of things to talk about, you’d make your way up and off my couch, telling me that you were going home. You’d wish me a good night, and I’d feel warm again. But this time, you sat in silence.

The vape pen sat awkwardly in between the two of us. I wanted to take another hit to deal with the tension in the room, but the silence paralyzed me. I found the courage to look up at you, and you turned and looked at me, staring straight into my eyes. I wanted so desperately for you to say something—anything—to break the silence. To make the moment end.

But you said only four words to me: “What do you think?”

I looked back down at the pen sitting between us. My gaze locked on the pen and away from you. I wasn’t sure how to read you. I had no idea what you meant. I had no idea what you wanted me to say either. Did you want me to say that I wholeheartedly approved? That I supported you in every decision you made? That I would wander through the desert, eating only quail and manna, just for you? I wanted to tell you what was really on my mind—how much I cherished you, what a constant source of light you were for me, how I so very deeply wanted to spend time with you, how I so desperately sought your approval, how worried I was that, even though Bella made you so happy, our nights together would slowly be replaced with nights that the two of you would have without me. But all I could muster was, “What do you mean?”

“I think you know what I mean,” you said, the sound of your voice trailing off and disappearing like a wisp of smoke.

I looked back up at you, and our eyes locked together once again. But this time, there was something so unsettling about your gaze. The soft, warm light I was so used to seeing from you turned harsh and terrifying, and instead of making me feel warm and happy, it made me feel vulnerable.

I didn’t want to keep looking at you. I didn’t know what else you wanted me to say. But from the way you had folded your hands in your lap and the way you were looking into my eyes so piercingly, there was only one thing I knew for certain: you knew.

You stood up. “I have to go,” you stammered. “I promised Bella I would come back again tonight.” You walked over to the door, turned the handle, and looked back at me one more time before leaving.

And that was the last time that winter that I would see you.

the sunrise

I tried to get over you. The sunrise would filter through my blinds, I would hide from the light under my sheets, and eventually, the sunset would pull me back into darkness. I had always turned to you when the sun set and surrounded me in darkness. After all, you were the one who made the sun rise for me. But for the first time, I couldn’t. I locked myself in my room and fasted for forty days and forty nights. I wandered through the desert alone, refusing to let those who loved me join me. I wanted the pain to leave my body, but all I felt leave me was violent sobs, the light in my heart quickly fading to a pitch black.

As the sunset faded back into darkness, so did I. I lost myself in it, feeling nothing. All this time, as I would wander alone, I would catch glimpses of the beams of light coming from your world, the land of milk and honey that I so desperately wished I could be living in. I would see you there, radiant, the light bouncing off your sun-kissed skin. You were always sitting on the sand, the girl of your dreams sitting next to you.

The two of you would remain like that, dipping your feet into the water, both of you swirling your feet around in it, your legs locking together to keep each other warm. And as you would, the glow from the sun would bounce off the water and back onto you. Every night, you would stay with her, and each time, you would both swirl your feet in the silky blue sheets of her bed. You’ve been holding her hand and trying not to let the world know that her reflection made your heart flutter.

Meanwhile, I’ve been lost in the darkness. I would curse your name as I would stumble through the desert, my heart sinking so far into the freezing sand that I could never imagine being warm again.

A friend who hadn’t seen me since I hid myself in the darkness told me to eat. I am filled with the power, she told me, to turn the stones weighing me down into bread to satisfy my hunger. Three times, she told me to get up. Three times, she told me there was so much to continue living for. Three times, she told me that there were so many people who loved me and cared about me, so many people who wanted to make sure that I was okay, who wanted to help me begin to feel better. But the first step was to leave my bed and eat again. I turned around in my bed, swaddling myself in my bedsheets. One does not live by bread alone, I said, but by every word that comes out from his mouth.

I couldn’t leave my bed no matter how much I wanted to. Every time I tried, my bed became a prison and the sheets paralyzed me. Every time I got close, I would take out my phone, ignoring the many texts others had sent me to try to check in on me, and I would see another picture that Bella had posted of the two of you, frolicking in the land of milk and honey while I remained shut out, forbidden by God from entering. I have let you see it with your eyes, I heard God say to me, but you shall not cross over there.

I could see the entirety of the beauty of the world that you lived in from the hill on which I was perched. In front of you was all the land of California: the beauty of the Pacific Ocean and its palm trees and beaches to the west, the forests on the mountains of the Cascade Region and the Sierra Nevada to the east, the picturesque farms in the Central Valley, and the red–orange sandstone rocks of the Mojave Desert to the south. She was still making you coffee every morning after you’d both rise from her bed. Meanwhile, I’d spend each of my nights alone, blowing clouds of heavy smoke into the night sky, hoping that with each exhalation, the pain would finally be dulled. In the dark of night, I would sit on the edge of the ocean, dipping my feet in the water and desperately wanting to feel hope again. But as I looked down, I couldn’t help but notice how much of my light was fading and how I couldn’t even see my reflection in the water anymore.

I was not always this empty. I used to be vibrant and filled with life. But ever since you left, everything wilted, and my heart returned to that graveyard of every love that I had ever hoped for, of every love that I had ever dreamed of. Every tombstone has the name of one of my loves that was never meant to be. And, my dear, there is a tombstone every step of the way. I was hoping you’d be different, that you would be the one to descend into the land of the dead I had been living in and bring about my salvation, ending this curse so I wouldn’t have to etch your name into the next unmarked stone.

But as I wandered through the desert, it was your glow, the radiance of your soul, that I would follow as I was trapped in the darkness. I followed the light that danced off your skin, the glisten in your teeth leading the way, the beams of joy dancing from your soul serving as my North Star.

***

Weeks later, as the barren winter trees outside my room finally began to blossom, I slumped back into my couch as I brought the pen back to my lips. I closed my eyes as I inhaled, and for a brief moment, as the smoke coated my tongue and barreled down my throat, I wasn’t thinking about you. But when I released the white, soft smoke back into the musty air of my living room, I heard a knock on the door.

“It’s me, Samuel,” you said through the door before I told you to come in.

“Long time no see,” I said as I set the pen down on the couch. You stood awkwardly by the side of the couch, the two of us completely silent. What was there to say after all this time? I sighed. “Do you… wanna smoke with me?”

You nodded and sat down, leaving enough space between us to fit at least another person.

I passed the pen back over to you, and you didn’t say a word. As you inhaled, you closed your eyes too. It was as if the two of us were both looking to escape our problems, even if just for a few seconds. All we desperately wanted was to forget our fears together. But what you didn’t know was that the only fear I wanted to forget was the fear of you being gone from my life again, that when I’d open my eyes after exhaling another puff of smoke, you’d be gone. Permanently this time.

When you exhaled, you forgot I was in the room and blew the smoke right in my face. As soon as you noticed what you did, you looked right in my eyes—the first time we made eye contact in months. Your almond-colored eyes were bright red, but they seemed softer than usual. As I waved the smoke out of my face, we burst into laughter.

“Shit, I’m sorry, dude,” you said, trying to suppress a cough or two. You stretched out your legs and leaned back on the pillows. And as you handed the pen back to me, you gave me the biggest grin I had seen on you in a while. “You know, this is great.”

I wasn’t sure what exactly you meant—maybe it was the high speaking?—but it was enough for me. “So, what’s new with you?” I asked, tiptoeing around how long it had been since we had last talked.

You told me how you ended things with Bella a week ago, how you fell out of love but how you were glad to be free and independent again. I asked you how were you doing, and you said everything still hurt, that you just felt numb and empty. You told me how you just couldn’t help thinking about her, from her dark brown hair with dyed-blonde tips to her beautiful smile to the way her body felt pressed up against yours. You had such an active imagination, you had told me once, and it was hard not to always be imagining her, wondering if she felt just as much hurt as you did, dreaming about whether she was happier now without you. “It’s so ridiculous,” you said to me. “Who just spends all their time thinking about someone they once loved?”

I got up and went to my kitchen, putting on the kettle and pouring us two cups of tea. I gave one to you, and your trembling fingers held the cup in your hand. But then you put it down on the table in front of you, not to take a single sip.

Have you ever just felt nothing for days? you asked me. Yes, I have, I told you. That’s how I’m feeling, you said. I put my hand on your shoulder. Well, just know, I said, choking back the hurt, that I’m always here for you. And then you gave me that big, goofy grin of yours as I moved my hand back to my lap.

You, too, had wandered through darkness. You, too, had a heart that was broken and bruised. We had so much in common, but you faced your pain in a land overflowing with milk and honey. You were the one who abandoned me in the desert, barring me from entering the light of your world. Yet as much as I wanted to hold everything against you, to exile you into the desert so that you could even begin to understand how much it hurt for you to abandon me, I couldn’t. It would hurt me too much. Instead, I brought the pen back up to my lips and just tried to enjoy the fleeting moment we had together.

For those brief few minutes, our worlds converged yet again. Our lives intersected just like they used to. I got to see the smile on your face that I so desperately needed. I got to see you again, the one who made the sun rise for me. I realized once more just how happy you still made me feel, that my heart would flutter just having you back with me. I wanted to drop everything and follow you to the ends of the earth, to allow myself to fantasize about a world where we could ever be together, just the two of us. I wanted to allow myself to slip into delusional bliss again just by seeing your smile.

But as soon as you left, I returned to my bed emotionally exhausted. I knew in my head and my heart that, as much as I was in denial, it was time to let you go. And so, I decided, on my own volition, to return to the graveyard of every unrequited love I’ve ever had, of every man who I was forced to let go of the fantasy of. I etched your name on the empty tombstone, left offerings of coffee beans and rose petals, and retreated back into the desert, telling myself that it was better for me to wander in the darkness than to live off the light that you created.

But that brief touch of your light was just enough to sustain me for a little longer.

my moon is not a moon & other poems

RICK LONGLEY

my moon is not a moon but a light inside a window on the ninth floor of an apartment block opposite to mine. my moon is not a moon but a goddess forever outside of my embrace staring at me from her featureless black balcony, floating over a mismatched carpet of buildings and lights and trees and the glimmering windows that belong to skyscrapers looming on the other end of the city. no matter how hard i try to fully close my bedroom curtains, moonlight always strikes my eyes drawing me to my windows, where i fill my lungs with cold nocturnal air and longing. listening, not replying, the moon has nothing to say to my sorrows, or maybe she's got too much on her mind ? she stares back at me with her ultra-white, enamel milk gaze, hoping i can hear her silent soul through telepathy. my moon is silver cutlery placed into a mirror, a queen -- surrounded by a hoarfrost halo and a boa of creeping bloodless, blue-black fingers tracing the chimney of a steam-engine train that charges past on invisible bridges, momentary shadows between myself and the moon. everything below her black ballgown will fall apart, reassemble and decay. rebuilt and destroyed, rebuilt and destroyed. all the while, my moon will merely dangle from a wire swinging in a room on the ninth floor of the apartment opposite to mine where there are never any people but ragged cloths on clotheslines, billowing in daytime desert wind. my moon is not a moon, but a metaphor which takes the form of an inside-out snowglobe, a crystalline vase, made of interwoven palm trees where i capture lovers, so i can chase them in the night, sweating peacocks and seagulls out of my floating island pores, running around the same three blocks again and again, stuck on repeat like the whole of humanity. i've flown across the oceans, in an aluminium missile, and when i looked out the window, you were still there, welcoming me to New York welcoming me to Moscow, when will i welcome you to my doorstep? when will i welcome you to my bed? only when there's an eclipse do you ever learn your lesson, thinking that i've left you, thinking that my patience has finally snapped, only then do you repent, only then do you ask for my forgiveness, and several minutes later, you pretend that nothing ever happened. moon, my moon, can't you see my tears? can you hear me crying in the night? i'm alone, i'm all alone in this world, give me meaning in this ever-changing carpet beneath your unchanging bedsheets. i wish to shine like all your glimmering children! i wish to fly like the midnight train running past your vanilla pillow skin! oh! what's that? the church bells, they're shattering your bones! the roosters are tearing at your flesh! don't go, moon! bathe your night in the fountain of youth! don't go! don't go!

a carton of midnight air the midnight air i swallow from my bedroom window tastes like milk and drowsy petrichor from half-remembered things echoes in the courtyard plates and dishes warmly clink the phantom thunder of an airplane i gulp the milky midnight air and shut the window the room seems very quiet now

looking at the stars and they'll write the same thoughts as i do with different combinations of symbols just as an aztec villager once dreamt this poem many moons ago, on the same night that an aboriginal tribesman looked up at the night sky and threw dirt on their dotted magnum opus, knowing they could never hide the stars from other artists' eyes.

Rick Longley

DISMEMBERING THE COSMOS: Insanity, Embodiment, and the Grammar of Flesh by

ANNA KIELTY

Bleeding Stars and Lunar Wombs: Aesthetic Disorders of the Medieval Body-Cosmos

The medieval body was not merely flesh, but celestial inscription: a trembling site where the firmament inscribed itself upon the viscera. To inhabit a body in the Middle Ages was to occupy a vessel both anatomical and astral, calibrated not by interiority alone but by the volatile harmony of the cosmos. Blood did not simply circulate—it responded. Bile did not merely sour—it signified. The four humours were not fluids but forces, a choreography of elements tuned to the errant music of planetary spheres. Madness, in this schema, was not deviation but dissonance: a melancholic fugue composed under the dark auspices of Saturn, or a lunar eclipse flickering behind the eyes. This essay begins in that interstice—between organ and omen, anatomy and astronomy—where disorder becomes aesthetic. To go mad in the medieval imaginary was not to collapse into incoherence, but to drift from celestial rhythm, to echo a discord written in the heavens. And this drift—often gendered, often feminised—becomes legible in image, text, and ritual not as breakdown but as cosmopoetic rupture. In the margins of illuminated manuscripts, hysteria sprouts as vegetal grotesque, saintly bodies burst into stigmatic excess, and the lunar feminine bleeds across calendrical time. Gothic architecture arches not toward God, but toward gravity: the melancholic downward pull of stone that dreams of ascension but mourns its own weight. The aesthetic field becomes a map of celestial malfunction. Sacred theatre, mystic vision, and manuscript illumination all stage the same epistemic drama: the failure of the body to mirror the sky—and the strange beauty that failure occasions. The humoral body is porous, gendered, and monstrously unstable. Black bile, especially, spills beyond its medical prescription into a symbolic economy of vision, madness, and melancholia—an epistemology of slowness, of sadness, of temporal excess. Here, Saturn presides not merely as planet but as aesthetic regime. The melancholic body is heavy not only with illness, but with insight. The madwoman becomes medium. The anatomised saint becomes relic. The womb wanders through the cosmos, not as aberration but as ontological critique. To read this visual and textual field, then, is to read an aesthetic of rupture: where sacredness and sickness converge, where gender bleeds beyond its liturgical scripts, and where madness is not silenced but staged—beautifully, terribly, and always in orbit. This essay approaches such materials not through a lens of pathology, but of poetics. Drawing upon feminist theory, phenomenology, medieval cosmology, and the grotesque, it seeks not to stabilise meaning but to trace its errancies, its gravitational pulls and lunar fugues. We proceed not linearly, but spirally—after Saturn, after the moon, after the mystic. What emerges is not a resolution, but a constellation: a gathering of fragments, images, disorders, and echoes that together illuminate the medieval body not as closed form, but as haunted firmament.

The Celestial Humoural Body — Flesh in Disarray

To imagine the medieval body is to enter a universe not of containment, but of correspondence. The body was never merely anatomical; it was elemental, environmental, astrological. It pulsed in concert with the macrocosm, a microcosm whose flesh was tethered to star and season, sacrament and sin. In this paradigm, sickness was not a breakdown of function, but a misalignment with divine design—a dissonance in the celestial score. And nowhere was this disharmony more evident than in the melancholic body: darkened by Saturn, drenched in black bile, and straining at the borders of rationality. The humoural theory, inherited from Galenic medicine and resanctified in medieval cosmology, rendered the body a fluidic sensorium. Its equilibrium depended on the balance of four shifting temperaments—sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic, melancholic—each with their corresponding planet, element, and gendered charge. But this balance was a fiction, and everyone knew it. The body’s default was fluctuation. It was a storm system of bile and blood, a lunar tide crashing against the womb’s porous walls. Woman, in particular, was imagined as humourally unstable: colder, wetter, and more susceptible to lunar sway. The uterus—unfixed, mobile, errant—wandered not only within the abdomen but across the cosmological map. Hysteria was not simply a disorder; it was an orbit. Madness, then, was neither failure nor exclusion. It was integration gone awry—a too-deep intimacy with the stars, a fevered misreading of the divine. In the medieval frame, melancholia possessed a peculiar ambivalence: it was both medical diagnosis and sacred exception. It made monsters and mystics of its sufferers. It made visionaries. The melancholic was not merely broken, but breached. Through the melancholic wound, something higher—more terrifying, more luminous—entered. We see this rendered with terrible grace in the visual culture of the period. In the Tacuinum Sanitatis, the body is diagrammed as agronomy: fluids as harvests, temperaments as seasonal fruits. In illuminated margins, grotesques proliferate—not merely ornamental, but epistemological. A nun births a demon; a bishop’s head erupts into flowers; women bleed from eyes and wombs simultaneously. These are not idle monstrosities. They are cartographies of humoural collapse—manifestations of internal imbalances erupting into aesthetic excess. The marginalia performs what cannot be spoken: the leakage of subjectivity, the feminisation of madness, the blurring of taxonomy between human, animal, and celestial. Architecture, too, partakes in this disorder. Gothic cathedrals do not express harmony so much as a yearning for it—their impossible height, their vaulting arches, their aching skyward thrust all testify to a world out of joint, gravity-defiant and weighted with sorrow. The Gothic is a Saturnine architecture. It broods. It weeps in stone. Its ribbed vaults resemble skeletal remains, its tracery like capillaries. This is not the architecture of health, but of sacred illness: a space structured around the void, the wound, the holy absence. Even sacred performance bore traces of this cosmological disorder. In Corpus Christi pageants, the divine body is consumed, dismembered, paraded. Christ’s bleeding becomes spectacle, transubstantiation becomes theatre, and salvation hinges on the audience’s aesthetic complicity in bodily rupture. This is not simply ritual—it is the dramaturgy of celestial breakdown, a humoral cosmology staged in public space. The Eucharist, with its transformation of flesh into bread, becomes the ultimate emblem of the porous body: mutable, feminised, unstable. To be mad, melancholic, or hysterical in this world was not to exit meaning, but to overflow it. The mad body becomes not void, but surplus: a site where the grammar of theology, medicine, and aesthetics momentarily collapses under the pressure of its own excess. This is particularly evident in the mystic corpus, where female bodies often become conduits for divine speech, not through stability but through fragmentation. Margery Kempe’s tears, excessive and unbidden, are not simply emotional—they are cosmological weather. Her weeping is a meteorology of the soul, an atmospheric language for a body permeable to the sacred. In this context, affect is not interiority, but transmission. Scholars like Caroline Walker Bynum have shown how female mystics refigured bodily suffering as spiritual authorship—how stigmata, bleeding, and fasting constituted a gendered epistemology. These bodies did not escape the humoural framework; they amplified it. They became altars of imbalance. Their sanctity emerged not despite their madness, but because of it. To return to the humours, then, is not to return to a “pre-modern” theory of medicine, but to a profoundly aestheticised cosmology—one in which gender, madness, and image are braided into a single, volatile epistemic fabric. In this schema, the body is not a stable signifier of identity. It is a process, a performance, a porous vessel whose fluids shimmer with metaphysical charge. In this first constellation, we have seen the humoural body as a kind of cosmic manuscript: written in blood, weeping margins, and planetary ink. Madness, melancholia, and femininity haunt this body not as aberrations, but as intensifications—instances where the cosmos becomes too much, too present, too close to the skin. This is the prelude to rupture, but also the prologue to vision.

Anatomies of Rupture — The Cut, the Relic, and the Gendered Flesh

If the medieval body was a cosmos in miniature—fluidic, astrological, mystically legible—then the early modern body, increasingly, became something else: an object. A volume to be opened, a problem to be solved, a surface to be violated in pursuit of truth. This shift was neither sudden nor total, but its violence was epistemic. To dissect the body was not merely to study it—it was to redraw the limits of meaning, to sever the flesh from the sky. The cadaver replaced the constellation. The diagram supplanted the star chart. What was once read in signs and humours was now incised with scalpel and stylus. Yet the logic of the cut was never neutral. To open a body—especially a gendered or racialised one—was to perform a ritual of knowledge saturated in power. Foucault’s Naissance de la clinique reminds us that the “clinical gaze” did not emerge ex nihilo. It was built atop the ruins of sacred embodiment. The dissecting table replaced the altar, but its liturgy persisted: the body must be sacrificed to be known. And this sacrifice, under Enlightenment regimes, was often feminised, colonial, spectral. In medieval hagiography, the body of the saint bleeds into miracle. Its fragmentation is sanctified. St. Catherine’s wheel, St. Agatha’s breasts, St. Margaret bursting from the dragon: all are tableaux of sacrificial flesh rendered glorious. But in the anatomical theatre, the dismembered body becomes mute. Its parts are indexed, numbered, catalogued—no longer relic, but resource. The shift from relic to specimen is not only ontological but gendered: the saint’s suffering once granted access to the divine, but the dissected woman grants access only to reproductive anatomy. Consider the mid-16th century anatomical fugitive known as “the Venus with the Opened Womb.” Her flesh peels back like petals. She is erotic, inert, impossibly passive—displaying her uterus like a reliquary. In her, we see a terrible synthesis: the aesthetics of sanctity fused with the epistemology of violence. Her body is no longer a site of vision or ecstasy—it is evidence. And this evidence is always gendered. The womb is no longer lunar or errant, as in the medieval imagination—it is mechanised, measurable, bound in wax. It has lost its mythos and gained a metric. But this new epistemology is haunted. The anatomical fragments do not rest. They return in dreams, in relic cults, in national mythologies. Tokarczuk’s Flights resurrects them. The dismembered organ—Chopin’s heart in a pillar, a preserved leg in a museum, a brain sealed in formaldehyde—becomes not proof, but question. These fragments speak not in certainty but in residue. They are not closure, but echo. In them, we see that dissection did not destroy the medieval body-cosmos—it merely repressed it. And what is repressed, returns. Indeed, the early anatomists were themselves part mystic. They believed in the sacred geometry of the body, even as they sliced it apart. The Flemish engravings of Andreas Vesalius tremble with devotional excess: the flayed man stands in an Arcadian landscape, gesturing toward heaven with one exposed hand, as if to say, “Behold the glory of my insides.” These images oscillate between the forensic and the ecstatic. Their violence is rendered in chiaroscuro. Their knowledge is baroque. But there is always a limit to what the cut can reveal. The melancholic soul cannot be dissected. The hysteria that travels from womb to throat eludes pinning. The anatomised body, though meticulously displayed, begins to shimmer with absence. The more it is shown, the less it yields. This is where the logic of modern anatomy begins to fold in on itself. As Jean-Luc Nancy insists, the body is never reducible to its organs. To touch the body, he writes, “is to touch the untouchable.” What anatomy claims to clarify, it also mystifies. Women, in particular, were rendered doubly mute in this regime: as subjects to be opened, and as witnesses to their own erasure. Their bodies served as both evidence and spectacle. The midwife was displaced by the male surgeon; the mystic’s bleeding was reclassified as hysteria. And yet, the feminine body refused to vanish. It lingered in the margins of anatomical illustration, in the iconography of martyrdom, in the baroque obsession with the fragmented corpse. The dismembered female saint and the wax anatomical Venus exist on the same aesthetic continuum—each a figure of disrupted coherence, each a site of epistemological vertigo. Thus, the body’s fragmentation becomes a counter-archive. Not a repository of knowledge, but of doubt. Not proof, but trace. A relic, yes—but of what? Of a time when the body was still written in stars? Of a cosmos where fluids and planets and gendered spirits moved in tangled harmony? Or perhaps of something still to come—a future body, not yet imagined, still dripping with metaphor, still open to the sky. In this section, we have lingered in the wound. The anatomical theatre, the saint’s fragmented corpus, the Venus of wax and waxen silence—all converge in a single epistemic tableau: a choreography of rupture. Here, dissection is not the end of cosmology, but its mutation. What was once astrologically legible is now anatomically exposed—but the longing for transcendence remains. The gaze has shifted, but the flesh still sings.

Celestial Bodies and Corporeal Madness — The Four Humours and Cosmology in the Space of the Mind

The medieval body, far from a fixed vessel, is a volatile nexus where corporeal substance, celestial influence, and psychic tumult coalesce. This intricate entanglement of flesh and cosmos underpins not only medieval medical thought but also a profound cosmology of madness—where the boundaries between body, mind, and starry heavens dissolve into a turbulent unity. The four humours—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile—were more than physiological fluids; they were the animating essences binding human being to the rhythms of the universe. Each humour corresponded to planetary qualities, elemental forces, and temperamental dispositions, creating a vast cosmic choreography in which the body danced to the music of the spheres. This choreography was inherently unstable. Health was balance—eucrasia—but this balance was never static; it was a continuous negotiation of forces, a flux of heat, moisture, and movement. Illness and madness emerged not simply as mechanical failures but as disruptions in this cosmic harmony. Insanity—mania, melancholia, hysteria—was thus read as an overflow or imbalance of humours, but also as a rupture in the body’s relation to the cosmos. To be mad was to be out of sync with the celestial rhythms, to live a body at odds with the heavens themselves. Crucially, the medieval understanding of the body’s relationship to space was not one of separation but of intimate participation. The microcosm of the body reflected the macrocosm of the universe: planets affected temperament; seasons shifted moods; astrological alignments guided diagnosis and cure. The body was a vessel of cosmic inscription, its humours the ink with which the stars wrote their influence. Madness, then, was a form of cosmic dissonance, a rupture that fractured not only psyche but also the body’s celestial inscription. As medical and cosmological knowledge evolved, these ideas did not vanish but transformed. The Renaissance and early modern period witnessed an increasing anatomical precision, yet the shadow of the humours lingered, suffusing medical and cultural imaginaries with lingering astrological resonance. The Cartesian body, disembodied and mechanistic, seemed to threaten this mystical entanglement, but popular and artistic cultures preserved the humoural cosmos beneath its clinical surface. The persistence of humoral thought is evident in how madness continues to be culturally framed in relation to bodily fluids and cosmic forces. Melancholia, for example, retains its association with creative genius and existential despair, its humoural origins refracted through modern psychology’s understanding of depression and bipolarity. Hysteria, once tied to the wandering womb, haunts contemporary discourses on gendered madness and psychosomatic illness, challenging Cartesian dualism and insisting on the body’s flux and porosity. Space itself, as a domain of human experience and imagination, becomes an extension of this humoural body-cosmos. The body in space—weightless, fluidic, and estranged from Earth’s gravity—reawakens ancient concerns about bodily balance and cosmic influence. The astronaut’s body is no longer firmly anchored but adrift, its humours metaphorically unmoored in microgravity’s strange affective and physiological regimes. The body in space re-inscribes the medieval cosmos in a new register: the disorienting dissonance of bodily fluids in flux mirrors the vastness and instability of the cosmos beyond. This overlap of corporeal flux and cosmic vastness echoes in cultural articulations of madness as well. The schizophrenic, the manic, the melancholic—these figures become cosmological as much as psychological, inhabiting spaces that blur internal and external, body and universe. Madness is thus not simply a medical condition but a mode of being-in-the-cosmos, a lived experience of celestial disarray and bodily fluidity. In sum, the medieval four-humour body, with its intricate cosmological and psychic symbiosis, continues to haunt contemporary imaginations of embodiment, madness, and space. Its fluid boundaries and celestial registers offer a potent framework for understanding how the body is never merely physical but always cosmological and affective, always caught in a dance of balance and rupture between earthbound flesh and infinite skies.

Celestial Palimpsests — Art, Literature, and the Medieval Body’s Cosmic Dance

To trace the medieval body in its celestial entanglements is also to traverse a rich landscape of artistic and literary imaginaries, where flesh and firmament become intertwined motifs, inscribed across manuscripts, paintings, poetry, and drama. These cultural texts serve as palimpsests upon which the shifting interplay of the four humours, madness, and cosmology is inscribed and reinscribed, revealing the enduring power of the medieval cosmic body to animate modern sensibilities. Medieval art, from illuminated manuscripts to anatomical diagrams, enacts a visual poetics of the humoural body as a microcosm of the universe. The Zodiac Man—a recurrent figure in medieval medical and astrological texts—embodies this synthesis: the body mapped with the signs of the zodiac, each limb and organ governed by celestial influence. This iconic image visually encodes the principle that human health and temperament are inscribed in the heavens, casting the body itself as a celestial manuscript. The vivid colors, intricate linework, and symbolic density of these images invite contemplation of the body as an ever-changing cosmic dance. Similarly, the illuminated Tacuinum Sanitatis—a medieval health handbook—illustrates the humours through lush botanical imagery and quotidian scenes, fusing the medicinal with the cosmological. These visual texts not only codify medical knowledge but also situate the body within a sensuous, lived world where cosmic rhythms pulse through earth and flesh alike. They invite a sensory engagement with embodiment, reminding us that health and madness alike are experienced phenomena, deeply textured and spatially situated. In literature, the humoural body unfolds across genres and epochs as a site where cosmic forces and psychic tumult are poetically rendered. Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales offers rich humoural characterizations—each pilgrim’s temperament and bodily constitution animated by the humours, from the sanguine Knight to the melancholic Physician—thus enacting a microcosm of medieval society itself, governed by the same cosmic principles. The bodily excesses and imbalances that mark their narratives are entwined with social, moral, and spiritual significations, underscoring how madness and health alike are culturally mediated. The Renaissance poet John Donne, whose work straddles the late medieval and early modern worlds, deeply inflects humoural and cosmological themes into his meditations on the body and soul. In Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, Donne reflects on the body as a mutable site where spiritual and physical elements interpenetrate, haunted by the tensions of mortality and transcendence. His imagery—of humours boiling, hearts weighing, and the soul’s flight—evokes a cosmos where inner turmoil mirrors outer vastness, echoing the medieval symphony of body and stars. In a different register, the visionary painter Hieronymus Bosch conjures a nightmarish cosmos where the boundaries between body and madness are grotesquely transgressed. His The Garden of Earthly Delights stages a cosmic tableau of human folly, where corporeal distortion and demonic chaos allegorize spiritual imbalance and cosmic disarray. Bosch’s work serves as a dark mirror to humoural cosmology, revealing the apocalyptic potential of bodily and psychic rupture when celestial harmony collapses. The symbolic potency of the heart as a cosmic and gendered emblem recurs across art and literature. The medieval tradition of reliquaries—chambers housing sacred bodily fragments, such as the heart of Saint Louis or the purported heart of Richard the Lionheart—transforms corporeal remains into loci of spiritual and national significance. These relics encapsulate the body’s fragmentation and reconstitution as a site of memory, identity, and transcendent meaning. The heart, as both organ and symbol, pulses with complex resonances of absence and presence, flesh and spirit, anchoring cosmic and personal narratives. Modern and contemporary artists continue to dialogue with this medieval inheritance, reimagining the body’s cosmic relations and psychic fractures through experimental forms. The Surrealists, for instance, deployed humoural motifs and cosmic symbolism to explore madness and desire, bodily fluidity and spatial dislocation. Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks and disembodied limbs evoke a universe where time, body, and mind dissolve into enigmatic flux, echoing medieval notions of instability and transformation. Similarly, the writings of Virginia Woolf—whose stream-of-consciousness techniques capture the body’s elusive interiority—can be read as a modern poetic rearticulation of humoural flux. Her characters’ shifting moods and embodied perceptions unfold as lived cosmologies, where psychic and somatic boundaries blur, and madness hovers as both threat and creative potential. Woolf’s work illuminates the perennial tension between coherence and fragmentation, order and chaos, that the medieval cosmic body embodied. Ultimately, these artistic and literary palimpsests articulate a poetics of the medieval body that transcends historical periodization. They insist on the body as a site of cosmic inscription and psychic complexity, a living constellation where humoural flux and celestial forces converge. Madness emerges not as mere pathology but as a profound mode of cosmic attunement and corporeal expression, inviting us to reconsider embodiment as a dynamic, multidimensional experience writ large across flesh and firmament.

Threshold Bodies — Ritual, Sacrifice, and the Affective Cartography of Space

If the medieval body was inscribed with the stars, it was also carved by ritual. The performative grammars of medieval life—exorcism, procession, mortification, healing rites—made the body not just a passive recipient of cosmic forces but an active participant in their realignment. The humours might flow from planetary malice or seasonal dissonance, but they could be recalibrated through rite. These bodies were not autonomous vessels but sites of negotiation—thresholds between the sacred and the profane, where flesh became medium, symptom, and symbol. Ritual in this sense was both liturgical and therapeutic. As in ancient pharmakon, it was cure and poison alike. The bleeding of the melancholic or the fasting of the humoral excess were not merely medical interventions but deeply cosmopoetic gestures—rituals that acknowledged the body’s subordination to larger, invisible currents. Foucault's archaeology of power finds unexpected continuity here: the “technologies of the self” in late medievality were bound to sacred temporality, not merely discipline. The humoral body was a body under ritual surveillance, its fluids policed by both clerical and planetary law. Yet ritual was not only regulation—it was also excess. One thinks of Bataille’s notion of sacrifice: the body as a sacred expenditure, a site where meaning erupts through destruction. In the medieval imaginary, madness frequently aligned with this sacred excess. The mad body might be read as a misaligned cosmology, but it also bore divine touch. From holy fools to visionaries, from demoniacs to anchorites, madness marked a threshold condition, a liminal subjectivity that exceeded both normativity and pathology. The mad were, in some sense, sacrificial figures—held at the edges of the polis, both feared and venerated, embodiments of alterity. This threshold condition maps directly onto the spatial poetics of the period. Consider the architecture of the cloister or the leprosarium, those paradoxical spaces that housed bodily fragility while orchestrating spiritual transcendence. These were sites of spatial liminality: enclosed yet open to divine influence, removed from the civic body yet central to its imagined purity. Michel de Certeau’s “practices of space” are helpful here—the mad, the sick, and the mystic moved through space differently. Their bodies didn’t just inhabit the world; they troubled it. They made space strange again. They drew sacred geographies where none had been drawn, sketching fugitive maps upon the surfaces of village, cathedral, forest. This is not metaphor—it is affective cartography. The medieval imagination mapped the world according to sensation and anomaly, not only to reason. Places had temperatures of soul. The woods could heal or hex. Water had memory. Stones absorbed sin. In this schema, the mad body was not out of place but differently placed, an alternative compass. Its dissonance was not dysfunction but reorientation: a painful, ecstatic recalibration of meaning. Hildegard of Bingen’s visionary mandalas—bursting with colour, geometry, vegetal flame—make this cartography explicit. They are not diagrams of madness but maps of a cosmos seen from within a body aflame with divine fever. From a contemporary perspective, such spatial-poetic constructions resonate with feminist geographers and phenomenologists. Sara Ahmed’s notion of “orientations” and Giuliana Bruno’s “emotional cartographies” echo the medieval intuition that bodies experience space relationally, erotically, historically. The humoral body is not a sealed system but a space of affective leakage. Madness, here, is not a failure of orientation but an alternative one—turned not toward productivity, but toward ecstatic entropy. It reclaims the body as a site of intensity, not utility. Even modern cosmology, in its speculative modes, returns us to this threshold poetics. Black holes, dark matter, non-locality—these are contemporary mysticisms, spatial-temporal enigmas that mock the stability of Cartesian extension. The medieval cosmos never died; it was displaced. In the language of quantum entanglement, in the poetics of dark energy, we hear again the voice of an older cosmology—a voice that spoke not in certainties, but in wonder, dread, and desire. To reapproach the medieval body, then, is not to rehearse a quaint past but to engage a radical ontology—one in which space, body, mind, and cosmos are tangled in perpetual negotiation. Ritual becomes the choreography of this entanglement, madness its most incandescent gesture, and art its memory trace. Through these entangled bodies—sacrificed, celebrated, estranged—we glimpse other ways of being in space, other grammars of flesh and divinity. Not a return to the past, but a spiralling toward it.

Echoes in the Void — The Medieval Body and Cosmology in Modern Imaginaries

The medieval body, so deeply entangled in the rhythms of the cosmos and the temperaments of the humours, has not vanished into history’s dust. Rather, it persists—ghostlike, spectral—in the contours of modern and contemporary imaginaries of embodiment, madness, and spatiality. This endurance is not nostalgic; it is transformative. The four humours, once the pillars of medical orthodoxy, reverberate as metaphorical registers of bodily flux, psychological complexity, and cosmic instability. The body’s ancient dialogue with the stars continues, now refracted through new optics of science, philosophy, and art. Consider the figure of the melancholic, still emblematic of creative torment and psychological rupture. The humoral body’s melancholia was once an ailment diagnosed by excess black bile; today, it haunts the aesthetics of existential angst and mental illness. The melancholic figure is no longer tied to planetary dominion but to cultural narratives of isolation, interiority, and alienation—modern forms of madness that echo the medieval liminalities between reason and frenzy, order and chaos. This persistence gestures toward the body as a porous site of psychic and cosmic tension, a liminal vessel both grounded and drifting, finite and infinite. In parallel, the legacy of humoural cosmology surfaces in contemporary scientific and philosophical engagements with embodiment in space. The body in zero gravity is not merely a biological organism but a shifting constellation of fluids, nerves, and perception. The fluid dynamics of weightlessness—blood pooling, bones dissolving, the inner ear’s recalibration—resonate uncannily with medieval conceptions of bodily instability and cosmic flux. To inhabit a spacecraft is to live the body as a microcosm adrift in a macrocosm, a fragile interface between terrestrial origins and celestial expanse. Artistic and literary imaginaries amplify this resonance. Sci-fi and speculative fiction reimagine the body as a vessel of cosmic contingency, a site where gender, identity, and sanity dissolve and reconfigure. The body in space becomes a metaphor for errancy, for the failure of fixed categories, for the poetic gesture of being unmoored. Here, the medieval humours morph into symbolic registers for the chaos and creativity of the human condition beyond Earth—fluid and mutable, precarious and luminous. Moreover, the history of cosmology itself is punctuated by moments where madness and embodiment converge in spectacular ways. The medieval cosmos was geocentric, ordered, hierarchical; modernity shattered this, fracturing the heavens and unsettling the body’s place within them. The Copernican revolution was not only astronomical but ontological—a dizzying dislocation of the body’s axis, a cosmic vertigo that echoes humoural imbalance. The madman’s gaze, once confined to melancholia and hysteria, expands into the stargazer’s wonder and the astronaut’s alienation. Madness and cosmology become intertwined trajectories of human estrangement and transcendence. At the intersection of these trajectories lies the uncanny persistence of bodily fragmentation and repair. Medical imaging and biotechnologies echo the early anatomists’ dissections, yet they also conjure new forms of corporeal multiplicity: digital avatars, cyborg prostheses, virtual selves. These are contemporary palimpsests where the body is continuously rewritten, much as the humoural body was inscribed by planetary influence. The boundary between body and cosmos blurs, reactivating ancient metaphors of flux, instability, and hybridity. In this continuum, the medieval body is neither simply archaic nor obsolete; it is a vital interlocutor with the present. Its languages of humour, madness, and cosmology inform ongoing questions about embodiment in an age of displacement—between planets, identities, and modes of knowing. The body, always already multiple, defies closure and coherence. It remains a constellation in flux, a site where the celestial and the corporeal dance in uneasy accord.

The Celestial Palimpsest — Bodies That Drift, Suffer, Refuse

To think the medieval body is to think a constellation: a figure inscribed not solely in flesh, but in heavens, in humours, in glyph and gospel. It is a body both literal and metaphorical, saturated with signification, oriented not by selfhood but by alignment—of stars, fluids, sins, saints. No stable boundary encloses it; it leaks, it weeps, it sings. It suffers. It dreams. It orbits. In this cosmological regime, to have a body is to be read: by the stars, by the Church, by physicians and poets. One is not so much a subject as a vessel—through which forces divine, planetary, and pathological pass. The four humours offer one such script, at once medical and poetic. Their fluctuations do not simply explain disease; they stage a theatre of temperament, an ontology of imbalance. Madness, melancholy, ecstasy—all find their roots not in interiority but in the moon’s pull, the womb’s movement, the liver’s bile. In this logic, insanity is not the failure of the mind, but its overexposure to the world. The humoral body is porous, forever in correspondence with the cosmos. The self is weathered, seasonal. Identity is not forged—it ferments. This instability becomes gendered almost inevitably. The female body, configured as moist, mutable, and weak, became both symbol and symptom of excess: too fertile, too leaky, too mad. The uterus wandered; the blood overflowed; the soul cracked open. But what emerges from these tropes is not simply misogyny—it is also metaphor. Medieval texts, both medical and mystical, return obsessively to the feminine body as a site of revelation. Pain writes itself most fiercely upon the skin coded female. Ecstasy ruptures most vividly through her. Her suffering is both suspicion and sanctity, her anatomy both burden and oracle. We have traced this drama across the mirrored surfaces of literature and medicine, of mysticism and dissection. From the anatomical theatres of early modern Europe to the textual raptures of female saints, the body becomes a site of both violence and vision. It is opened to be known, but it resists the gaze. It bleeds significance. It unravels. And in this unraveling lies not a loss of meaning, but a proliferation. The body, once mapped according to stars and humours, re-emerges as a space of polyvocality: where cosmology, theology, and poetics blur. Pain, especially, becomes a language of radical potential. Not simply symptom or punishment, but text. For mystics, it is divine syntax. For feminists, it is an epistemology. In suffering, the body declares what cannot be captured in doctrine. It performs a truth that bypasses reason. The wound becomes a mirror. The scar, an archive. And this archive does not cohere—it refracts. In Margery Kempe’s floods of tears, in Hildegard’s visions, in Catherine’s ecstatic self-disintegration, pain transcends its own limits. It transforms the body into a cosmograph, mapping not place but passage. This essay has sought not to stabilise the medieval body, but to allow it its movement—its drift through texts, through systems of knowledge, through metaphysical climates. The madness of the melancholic, the visions of the mystic, the dissected limbs of the anatomist, and the spilled humours of the female sufferer all index a world in which knowledge was less a possession than a weather pattern: unpredictable, alchemical, devout. Foucault’s clinic, Butler’s performance, Bergson’s durée—all echo across these medieval scenes, not as anachronism but as resonance. What Tokarczuk performs in Flights, in the anatomy jars and the drifting narrators, is a re-enchantment of this medieval script—where motion replaces meaning, and the body becomes a spiral, not a system. If the modernist body is closed—anatomised, surveilled, psychologised—then the medieval body is open: to heaven, to flame, to madness, to grace. It is a body that contains contradiction without resolution, that performs gender while undermining it, that bleeds humours and produces metaphors. It is as much allegory as organism. And in its refusal to settle into coherence, it offers us a model of thinking—of being—that privileges fluidity over fixity, rupture over reason, gesture over ground. What remains, then, is not a body but a grammar. A way of reading flesh as text, as myth, as cosmos. And within this grammar, we are permitted to ask different questions—not what a body is, but what it means to move through one; not what gender delineates, but what it performs; not what pain signifies, but how it speaks. These are not medieval questions alone—they are enduring ones.

MANCHESTER SPRING

HANNAH LEDLIE

PEBBLES AND OTHER POEMS

SANDEEP KUMAR MISHRA

Pebbles Time smooths rainbow hardness of tree basalt, vermilion jasper, silvery granite and pale feldspar with the help of humdrum but patient jeweller of tides. Volcano-born, earthquake-quarried, heat-cracked, wind-carved, death shapes compact among the rocks, It drifts light as a fractured bone. When the tide uncovers, it blinks among the smashed shells. Upset by gulls, bleached by salt and sun the broken crockery of living things. An eagle surveys from the upland, unsympathetic to the burdens I have carried here, The sea would not hug me, so I sit, hollow as driftwood, jumbled as pebbles.

O' Stars! When I goggle at the screen of wild black yonder, O stars! I feel a blazing avidity in my vital limbs. Elan eyes of the angels, invested in with thousand finesses, show your cloudless sparkle to the ignorant world. The magnetic star adjacent the moon guides the sailor way out. My heart responds to thy flickering with life and ignites my bituminous soul with an immortal spark.

First Monsoon Immigrant pregnant clouds in this high time preparing to deliver aerial showers. Huge watery vessels, like a developed baby Too heavy to hold in atmospheric womb. With lightening proclaiming over the vastness of the supply of life fluids, Weary peasants’ restless eyes wait for their intimate dark relatives.

Winter In snowy unpigmented drape wintry withdrawn world waits for the warm kiss of the day. Through the long lonely valley the elevation blows the glacial gale to cheer the deep and solemn solitude. Over the bare upland, a pious sunbeam plays when the heartless west extends its blast but the stormy north sings sleet. All the field lay bound beneath a crispy integument of snow, It withers all in silence to expose the earth and show its susceptible skeleton life. I walk to crash crunch beneath my feet to see a dancing darkness in vivid blue. In an ecstasy the earth drinks the lukewarm silver sunlight. The beast or bird in their covert rest, These leafless trees resemble my fate, as a lonely robin with its burning breast sits in subtle sweetness of the sun. How ruby banner of poppies spread where the lilies fell asleep but the rose’s hearts are beating still. When the fresh sap of earth finesse the flaxen flowers, The snowflakes swarmed in the yard to beat the feeble window panel. When I step in warm chamber, I wonder how like me the grief worn threshold stone was? Distorted and shivering shadows are upon the dim lighted ceiling. The colourless clusters of lacklustre stars ornaments the night bride. The lenient liquid moon slides through bare black branches. A chamber corner draft swept the night stand, The cruciform contour of winged craving took a fleety flash flight, I swear to keep every sweet promise under a warm furry blanket of seed prospect. God pity all those homeless souls.

Morning Ecstasy Reluctant night slowly retreating, Grey earth, some dim shades still hovering. Dawn strides out leisurely to wake every farm Sleepy sun with liquid light makes the sand warm. Morning nymph rising from the ocean of pearls wearing magic mist mantle as the wind swirls her gleaming bracelet. Borrowed from sun rays swiftly up to the hilltop her glory sways. Her fragrance wakes up the slumbers of mortals, The crowing birds but break the silence acetals. I am eager to rise earlier than the bee, Perhaps to feel the divine power if it be. Every home kindles its necessary fires, Sense morning incense, listen far sounding lyres. The soul feels fresh and rejuvenated as healing light exhaled a divine incarnated. The bunches of roses and the lily awaken, The wind hides in trees, makes them shaken. Shy maid advances with pitcher to fill in river, The peasants and herdsmen on their way as ever, All creatures must toilsome courses run hard Because untrodden the path, bright is the reward.

SANDEEP KUMAR MISHRA

THE SUN MOON STARS AND ME

SARA FARNWORTH